Update 4/11/20 12:00 PM EST — After publication of this story, the NTIA published a letter to the FCC that included the notes Norquist, Deasy and Griffin, and the memo from Luu. In addition, the NTIA associate administrator said it is his belief that the FCC cannot “reasonably reach” the conclusion that the Pentagon’s concerns have been resolved.

For the latest updates to this story, click here. The original story is below.

The Federal Communications Commission is poised to approve a draft order as soon as today that would reallocate a specific portion of the radio spectrum for broadband communications, overruling a decade of strong objections from the Department of Defense.

Senior Pentagon leaders warn that such a move will lead to “unacceptable” harm to the GPS system by creating new interference that could disrupt satellites critical to national security.

The decision, described by multiple sources to C4ISRNET, would allow the privately held Ligado Networks, formerly known as LightSquared, to operate in L-band frequency range despite years of government resistance, largely led by the DoD.

The emphasis comes amid renewed focus on 5G technology from key White House administration officials.

Sources say the drive to approve Ligado is coming from the White House National Economic Council. That office is led by Larry Kudlow, who has expressed interest in the economic benefits of expanding the nation’s 5G capabilities.

In addition, Attorney General William Barr announced April 7 he will lead a new national security group known as “Team Telecom.” Barr, a former telecom executive, has also talked about expanding the United States’ 5G capabilities — or next-generation mobile communications technology — as a way to fend off China’s dominance in the sector.

A source familiar with the proceedings said “the approach being considered provides protection to government GPS orders of magnitude above the point at which there would be harmful interference, while advancing America’s economic and national security interests and leading the world in 5G.”

If approved, the Ligado draft order would appear to override concerns from the DoD that Ligado would cause “unacceptable operational impacts to the warfighter” while promising a solution that is “not feasible, affordable or technically executable,” according to the Pentagon.

Other experts, who see Ligado as a way to help boost the economy and to help compete with China, claim that the Defense Department’s analysis does not show that interference is a certainty.

The DoD, the White House, and the National Telecommunications and Information Administration — which is part of the Commerce Department — declined to comment for this story. The FCC did not return a request for comment by press time.

A yearslong fight

For roughly 10 years, officials from Ligado, and its predecessor LightSquared, have tried to get approval from the Federal Communications Commission to use part of the L-band spectrum for communications.

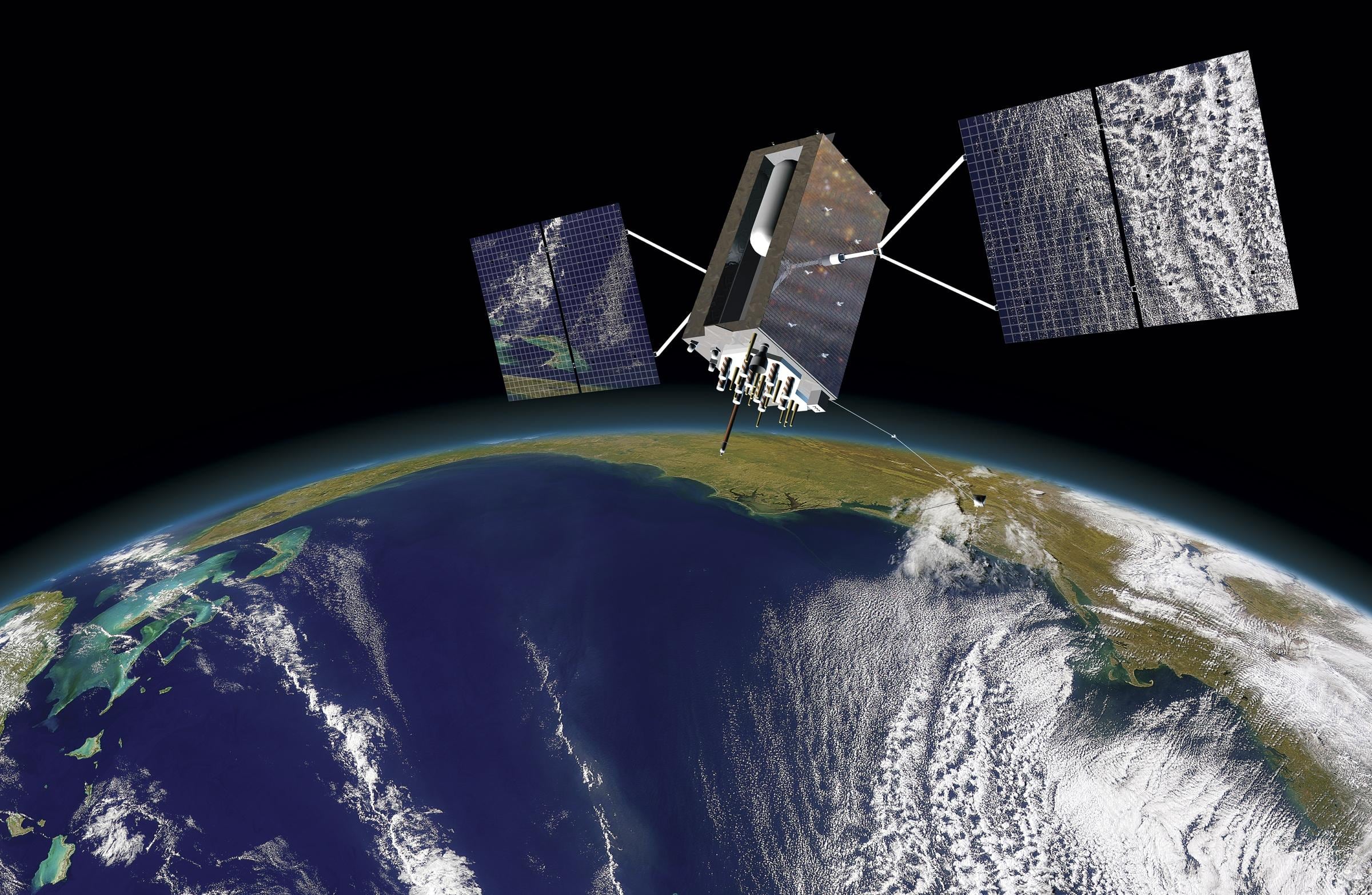

L-band is described as the range of frequencies between 1 to 2 GHz. GPS, and other international navigation systems, rely on L-band because it can easily penetrate clouds, fog, rain and vegetation. Ligado owns a license to operate the spectrum near GPS to build what the firm describes as a 5G network that would boost connectivity for the industrial “internet of things” market. The company uses the SkyTerra-1 satellite, which launched in 2010 and is in geostationary orbit, and it has planned to deploy thousands of terminals to provide connectivity in the continental United States.

Many federal government leaders, including those from NASA, the Federal Aviation Administration, the Department of Transportation, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, worry about the proximity of that spectrum to the radio frequency used by GPS satellites.

In an op-ed for The Hill newspaper in 2017, former FCC Commissioner Robert McDowell said the decision would be akin to “allowing a frat house (LightSquared) to move into the lot next to an already established library (existing satellite licensees), which needs a quiet neighborhood to operate.”

RELATED

Some satellite operators, including Iridium, whose services are used by the DoD, are also worried about potential interference from Ligado.

But perhaps nowhere has the opposition been greater than at the Pentagon. The Air Force’s GPS satellites underpin the Pentagon’s information advantage in position, navigation and timing. GPS is used for targeting, weapons guidance and reconnaissance. In addition, the department has spent tens of billions of dollars on the satellites and associated ground systems in the last several decades.

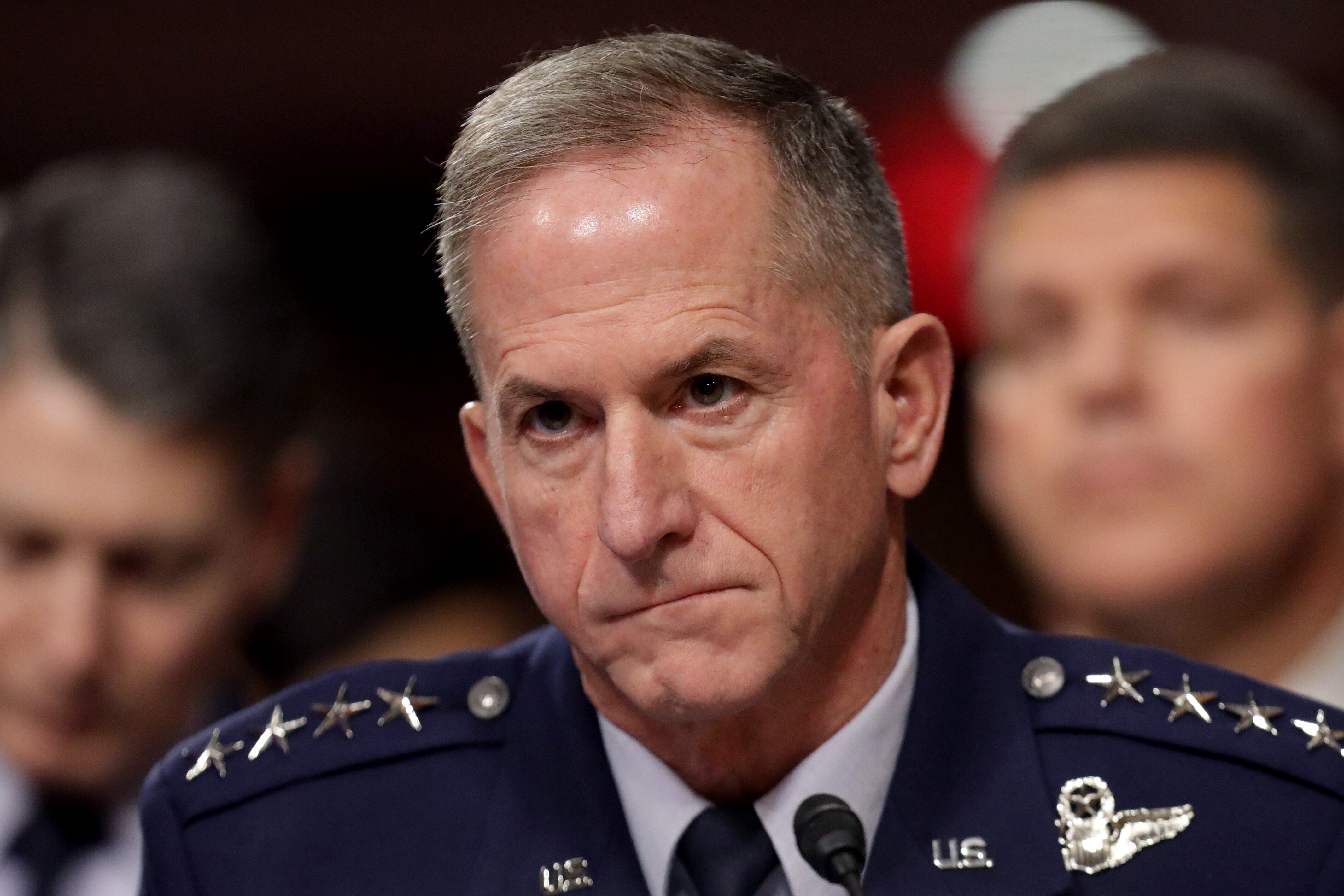

Discussion about LightSquared’s impacts appeared during congressional hearings as far back as 2011, but the most recent public concern within defense committees about the issue came during a March 15, 2016, hearing. During testimony before the House Armed Services Committee’s Strategic Forces Subcommittee, Gen. John Hyten, then the head of Air Force Space Command and now the vice chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, worried about Ligado’s impact on GPS, saying: “We cannot do something that will infringe on our national security, period.”

RELATED

In December 2018, the National Executive Committee for Space-Based Positioning, Navigation, and Timing recommended against approving Ligado Networks’ request to use the spectrum. In April 2019, then-acting Defense Secretary Patrick Shanahan sent a letter to the FCC recommending it reject the company’s proposal, while now-Defense Secretary Mark Esper sent a similar rejection request in November 2019.

The most recent push by the DoD began with a Feb. 14 memo, written by Thu Luu, the Air Force’s executive agent for GPS. The memo was co-signed by representatives from 12 other agencies, including NASA, the Federal Aviation Administration, and the departments of the Interior, Commerce, Justice, Transportation and Homeland Security. Officials sent the memo from the DoD to the Interdepartment Radio Advisory Committee, an office inside the Commerce Department that oversees the spectrum that enables America’s GPS capabilities.

On March 12, Michael Griffin, the DoD’s head of research and engineering, and Dana Deasy, the department’s chief information officer, sent another letter, with the memo attached, this time addressing an office inside the National Telecommunications and Information Administration, or NTIA. The two officials reiterated the concerns in the memo and twice asked that it be entered into the public record, as the information would be “critical” to any decision made on Ligado.

Then, on March 24, the Pentagon escalated its concern to a higher level, through a letter from David Norquist, the department’s No. 2 official, to Wilbur Ross, the secretary of commerce. Once again, Norquist asked that the information be sent to the Federal Communications Commission’s panel in charge of making a decision on the Ligado case.

But weeks later, there is no sign of the department memos in the FCC’s public docket, which sources say is due in part to pressure from Kudlow’s office, the White House National Economic Council.

Technical concerns

Over the years, Ligado officials have argued their system would use less spectrum, have lower power levels and reduce out-of-channel emissions. In the face of complaints from major commercial GPS companies such as Garmin and John Deere, Ligado has also offered to reduce the amount of spectrum it had initially planned. The company has also said it will work with government agencies to repair and replace equipment if necessary.

At the same time, proponents have argued that the NTIA, not the Pentagon, oversees spectrum use for the executive branch.

However, in a Dec. 6 letter, Douglas Kinkoph, the acting deputy assistant secretary for communications and information at the Commerce Department, said the NTIA is “unable to recommend the Commission’s approval of the Ligado applications.” He cited the DoD’s opposition as well as other 5G efforts in the letter.

Concerns among the DoD and other government agencies have not calmed since then.

Luu, the Air Force’s executive agent for GPS, wrote in the Feb. 14 memo that it would be “practically impossible” for the DoD to identify the impacted receivers and replace them without investing “significant time and resources to effect software modifications, trial and testing, and validation.” She specifically cited a 2016 test at White Sands Missile Range in New Mexico, the results of which are classified.

Part of the problem stems from the fact that some older GPS receivers “listen in” on signals next door, meaning those in the Ligado spectrum, according to 2012 testimony. As a result, DoD officials want a small margin of error when it comes to interference. But Ligardo’s supporters argue the Pentagon’s standard is unnecessarily stringent. The FCC proposal will suggest a wider margin of error for interference outside of the GPS spectrum — a win for L-band proponents.

Luu argued that any mitigation plan put forward by Ligado will be “impractical and un-executable in that they would shift the risk of interference to, and place enormous burdens on, agencies and other GPS users to monitor and report the interference. … Ligado’s proposal to replace government GPS receivers that are affected by its proposed network is a tacit admission that there would be interference.

“Additionally, the mitigation proposal by Ligado, even if technically feasible, only covers those receivers owned by the government and would leave many high-value federal uses of civil GPS receivers not owned by the government, such as high precision receivers, vulnerable to interference, as Ligado has admitted in its filings.”

Even if such a solution was shown to work, it could take “on the order of billions of dollars and delay fielding of modified equipment needed to respond to rapidly evolving threats by decades,” Luu said.

‘Free market’ principles

Now, despite the DoD’s national security concerns, it appears Ligado is on track to receive its authorization, perhaps as soon as April 10.

What changed, according to the sources who spoke to C4ISRNET, is both a growing interest from the White House in the economic and political benefits of expanding 5G capabilities, as well as an increased sense in parts of the government that the GPS concerns may be overblown.

“Fortunately, it has been proven time and time again that Federal users can reduce their spectrum holdings without putting at risk their vital missions. Nonetheless, these same entities, especially the Department of Defense (DoD), which is the largest holder of the most ideal mid-band spectrum, are exceptionally reluctant to part with one single megahertz,” FCC Commissioner Mike O’Rielly said in an April 8 letter to President Donald Trump. “Simply put, every excuse, delay tactic, and political chit is used to prevent the repurposing of any spectrum.”

Ligado has repeatedly pushed the FCC to make a decision on its approval, saying it is integral to the advancement of 5G services in the United States. That argument has gained traction with those concerned about China’s growing 5G capabilities, which Beijing has used to gain political leverage across the globe.

Some, such as Attorney General Barr, have argued it’s long past time for the FCC to decide the issue. In a Feb. 6 speech, he said that “by using the L-band for uplink, we could dramatically reduce the number of base stations required to complete national coverage. It has been suggested that this could cut the time for U.S. 5G deployment from a decade to 18 months, and save approximately $80 million. While some technical issues about using the L-band are being debated, it is imperative that the FCC resolves this question.”

The new “Team Telecom,” stood up by an executive order from Trump, is tasked with reviewing and assessing “applications to determine whether granting a license or the transfer of a license poses a risk to national security or law enforcement interests of the United States.”

While Barr is chair of the new group, it does include a seat for the secretaries of defense and homeland security, among others.

In an op-ed for the Wall Street Journal in January, former NASA Administrator Dan Goldin said “more than 5,000 hours of testing has shown there is no harmful interference to GPS. This isn’t a technology problem; it’s a bureaucracy problem. … [I]f we do not accelerate the deployment of U.S. 5G now, we risk the very economic, national security and technological leadership we endeavor to protect.

Doug Smith, the chief executive of Ligado, asked the FCC in February for approval, saying it had waited four years for the commission to vote on a proposed spectrum plan that would help Ligado build the network it needs.

“The FCC already has all of the information it needs to make an informed decision that is in the public interest. The FCC should decide the matter promptly so that we do not miss this opportunity to advance the future of 5G in America,” a Feb. 20 letter read.

That argument may be behind the interest in the company from Kudlow’s office, the sources said. Kudlow, in his role as economic adviser to Trump, is hoping for an economic turnaround following the new coronavirus pandemic, and has expressed a desire to grow America’s native 5G capability.

Before the COVID-19 outbreak, Kudlow was planning a major 5G summit at the White House, tentatively for sometime in April, which was planned to include a mix of major telecom players and a handful of smaller firms — another sign of the administration’s interest in 5G.

Speaking at an April 2019 event, Kudlow indicated it was the White House’s preference to apply “free market, free enterprise principles” to building 5G capabilities.