This is the first of a three-part series on the Navy’s struggles to develop unmanned ships and systems.

WASHINGTON – After a bruising, year-long fight with Congress, part of the Navy’s plan to field unmanned ships appears to be on life support, making 2021 a crucial year for plotting a path forward.

In the 2021 appropriations and policy bills, lawmakers eviscerated funding for the Navy’s Large Unmanned Surface Vessel (LUSV) development program and laid in stringent requirements for the Navy to work out nearly every component of the new vessel before moving forward with an acquisition program. In all, lawmakers slashed more than $370 million from the $464 million the Pentagon requested.

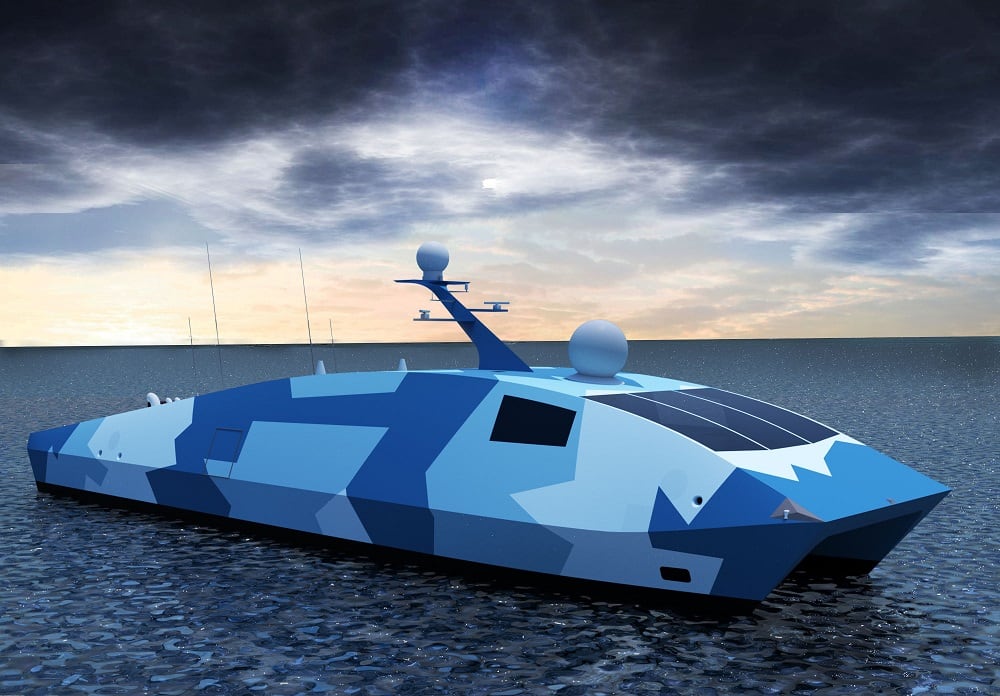

The LUSV is supposed to be the Navy’s answer to a troubling problem: How does the service quickly and cheaply field hundreds of new missile tubes to make up for dozens of large-capacity ships due to retire over the coming years? But Congress is not convinced the Navy did the proper analysis prior to launching into a technically risky, 2,000-ton robot ship.

Before going any further, the Navy must conduct a full study examining alternative approaches for fielding missiles downrange.

The LUSV has become a flashpoint for a larger problem: After two decades of high-profile problems with programs such as the littoral combat ship and the Ford-class carrier, Congress’s faith in the Navy to make significant technical leaps without close supervision has all but evaporated, according to more than two dozen interviews, roundtables and conversations with knowledgeable sources over the past several months. Furthermore, it is unclear that, even if the Navy managed to make the LUSV related technologies work, it would be the right answer for the missile tube problem.

RELATED

Now the Navy enters 2021 with its LUSV funding slashed and knowing that Congress doesn’t trust it with basic technology development.

“We fully support the move toward unmanned, whether that’s on the surface or undersea.” said Rep. Joe Courtney, D-Conn., who chairs the House Armed Services Committee’s sea power subpanel. “But we want to make sure ... the real nuts-and-bolts issues … are worked out before we start building large, unmanned platforms.”

Navy leaders insist they are fully committed to bringing the Navy into a future that incorporates unmanned ships, but sources both inside and outside the service, as well as analysts who spoke on the record, agreed the Navy has not come up with a convincing concept of operations for the ship. And while the prototyping effort will continue this year, the Navy will have to decide whether it needs to change course entirely.

Navy leaders appear poised to build a year delay into the LUSV program according to an early version of its 2022 shipbuilding plan released in December, but the future of the program is in some doubt. Since last year’s National Defense Authorization Act, Congress explicitly forbade the Navy installing its ubiquitous MK 41 VLS launcher on its LUSV prototypes.

The newly enacted 2021 NDAA forces the Navy to explore several new options for fielding VLS cells on surface vessels beyond its current preferred LUSV.

The law calls for a year-long study to explore “the most appropriate surface vessels to meet applicable offensive military requirements … including offensive strike capability and capacity from the Mark 41 vertical launch system,” the text reads.

The analysis is to explore “modified naval vessel designs, including amphibious ships, expeditionary fast transports, and expeditionary sea bases; modified commercial vessel designs, including container ships and bulk carriers; new naval vessel designs; and new commercial vessel designs.”

In other words, the Navy is to cast a wide net in coming up with options fielding missile tubes afloat.

What’s the big deal with VLS cells?

Experts agree if the Navy can’t find a quick way of fielding more VLS tubes, past mistakes in shipbuilding programs will catch up to the service as high-capacity ships built in the 1980s and 1990s retire and are replaced with smaller ships with less missile capacity.

That’s a problem if the Navy thinks it may need to go toe-to-toe with the world’s largest navy – China – in China’s own backyard where it is protected by a formidable land-based anti-ship rocket force, which is what drove the Navy toward the LUSV in the first place.

“What’s driving the urgency is the presence of a very capable Western Pacific adversary,” said Bryan McGrath, a former destroyer captain who runs the defense consultancy the FerryBridge Group. “Pure and simple.

“Secondly, on the horizon there is a situation where we’ll be trading guided missile submarines, cruisers and destroyers for Constellation-class frigates,” McGrath said, referencing the new FFG(X) program that will field a VLS launcher less than half the size of a destroyer. “And that puts you in a situation where you will be losing [vertical launching system] tubes.

“So, a relatively cost-effective and efficient way of increasing VLS tubes in the fleet is the Large Unmanned Surface Vessel.”

As the fleet’s cruisers, destroyers, and attack and guided-missile submarines reach the end of their lives, the Navy’s striking power will start to precipitously decline at just the moment the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy reaches new heights. The U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence projects China will have a fleet of 425 ships by 2030, compared to a U.S. Navy fleet that has struggled to maintain any more than 300 ships.

Furthermore, the Chinese Navy is concentrated in the Western Pacific, whereas the U.S. Navy’s smaller fleet is divided between two coasts.

The U.S. Navy has a rapidly contracting window to avoid a decline in both the number of vessels it can field and its striking and defensive power, according to an analysis by Defense News based on public Navy records, records obtained by Defense News, public statements from the service, data on the expected service lives of Navy ships, and a recent report from the Hudson Institute on a future fleet construct.

That will put pressure of the Navy to field something, anything, to turn the tide.

This contraction can perhaps be best illustrated by the number of vertical launching system missile tubes capable of carrying weapons the size a Tomahawk cruise missile. For example, consider that by the early 2030s, the Navy will have decommissioned all 22 of the Ticonderoga-class cruisers, each with 122 VLS missile tubes onboard, along with all 21 of the first-generation Arleigh Burke Flight I destroyers, each with 90 VLS cells.

Between the cruisers, the first-generation Arleigh Burkes, the Ohio-class guided-missile submarines and the Los Angeles-class submarines, the Navy stands to lose about 70 ships with nearly 5,500 VLS cells. Today, based on the last official 30-year shipbuilding plan, it appears the Navy will replace those ships - and their tubes - with around 65 ships and submarines that have anywhere from 1,800 to more than 2,000 fewer VLS cells.

That means if the Navy doesn’t move quickly to offset the loss, the ships it plans to commission will field from 32 to 37 percent fewer VLS cells than the ships being decommissioned by the early part of the next decade.

These numbers do not factor in the draft FY22 30-year shipbuilding plan released in December, which is all but certain to change under the Biden Administration.

What is it good for?

After two years of funding cuts and restriction placed on LUSV, an even more fundamental issue is emerging: Is LUSV even a good idea?

The Navy is seeking to field more technologies that allow the fleet to spread out over a wider area instead of operating aggregated around an aircraft carrier or a large Marine landing force.

Navy leaders believe operating this way would make concentrating against American forces in the region difficult and would tax China’s intelligence, surveillance and targeting networks by presenting more complicated threats in more places. The concept is called “Distributed Maritime Operations.”

The idea behind LUSV is to make it a faithful wingman that tags along with larger manned platforms and works as an adjunct missile magazine equipped with the Aegis Combat System working with a manned warship – like the new Constellation-class frigate that is being built with a high-end sensor suite and 32 VLS cells.

With enough LUSVs, the unmanned vessel could detach from the ships it is accompanying after expending its missiles and a new, fully loaded LUSV could join the force to take its place.

But even if the Navy could get the LUSV right, might the downsides of encumbering Navy forces operating in dangerous waters with a slower, un-crewed warship outweigh the benefits?

RELATED

In a September roundtable with reporters, Vice Adm. Jim Kilby, the Navy’s top requirements officer, told reporters that the LUSV is about finding ways to field technologies that cost less than traditional surface combatants.

“My view as an operator, as a person who thinks about the adversary and long durations of potential conflict, it adds depth to my bench,” Kilby said. “It allows me to position my forces and rotate my forces in a manner that that I wasn’t able to before in a more distributed and probably more cost-effective manner. Because I believe LUSV will be cheaper, ultimately, than a [destroyer] or even a frigate for that matter.”

But questions persist. How would the Navy maintain a fleet of LUSVs? Where would they be based? How many shore-based sailors will the Navy need to maintain them? Should they be designed to operate from overseas bases or should they be designed for transoceanic transits, significantly increasing the costs and reliability concerns?

The stack of unanswered questions only fuels larger doubts from lawmakers, and even those inside the Navy and in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, that this platform may not be the right answer, said Bryan Clark, a senior fellow at Hudson Institute who worked with the Navy and OSD on a recent fleet architecture study.

“People are not sold on the viability of that approach even if it works technically, which means there’s a lot less energy behind it,” Clark said. “With Aegis, or the ballistic missile submarine, or nuclear power: with every one of those advancements you could clearly see on the backside, if it worked, then there would be enormous improvement possible in capability or capacity.

“I don’t think anybody thinks the engineering here is going to be completely impossible. The problem is they’re not completely sure that even if you could build and operate this ship that it’s right answer.

“That’s the nagging fear a lot of people have: Do we want to dump all this money and time into this project, only to find that there’s no concept of operations that works?”

‘Experiment and demonstrate and prototype’

The Navy is convinced, however, that investments in unmanned systems are vital if the fleet is to be in more places at the same time with more sensors and weapons at its disposal.

“The manpower on ships is a costly thing for us,” Kilby said in response to a question from Defense News. “So, if we can figure out a more efficient way to add more platforms to the manpower we have, we can make our force more flexible.

“We shouldn’t talk about the LUSV in a vacuum. I view unmanned surface vessels as a complement to our man surface vessels. I think initially we say the LUSV will [augment our VLS capacity], but I think it will have secondary and tertiary benefits that we can add on to it as we experiment with it and learn about it.”

Inside the effort to develop prototypes, the Navy has been pleased with progress in the ongoing LUSV industry study.

The Navy in September awarded $7 million contracts to Austal USA, Huntington Ingalls Industries, Fincantieri Marinette, Bollinger Shipyards, Lockheed Martin and Gibbs & Cox to work through LUSV issues and mull possible designs.

The work has revealed both further issues with the program but has also produced substantive ideas on how to make progress on reliability in the propulsion plant, in the communications system, and with the autonomy concerns, according to a source familiar with the effort. Even a skeptical Congress is letting the Navy push ahead with funding for work on autonomy, command and control, elevated sensors and experimentation associated with the LUSV program, according to the text of the recent Defense appropriations bill.

Congress also redirected more than $55 million in LUSV funding toward further development of the Medium Unmanned Surface vessel, money the Navy did not ask for.

The idea behind the Medium Unmanned Surface Vessel is to put sensors into places that need constant monitoring for submarines or surface traffic without expending a destroyer that could be used for much higher-end missions. The Navy has been experimenting with a prototype MUSV, Sea Hunter, and will take delivery this year of the second vessel in that experimental class, the Seahawk, the source familiar said.

Furthermore, the Navy has sent an initial unmanned surface vessel prototype developed by the Special Capabilities Office to the new Surface Development Squadron in San Diego, and the second prototype will be in California by the end of this year, the source said.

Navy leaders believe that they will need unmanned platforms in large numbers if the fleet is to square off with a much larger Chinese fleet playing a home game in its regional waters. Whether armed large, unmanned surface combatants factor into that will depend on the outcome of its experimentation, said James Geurts, the Navy’s head of research, development and acquisitions in the September roundtable.

“It’s not a debate of: Can unmanned systems add value? They’re doing it every day for sailors or Marines all around the world. But question then becomes, ‘Where do they add value?’

“Do I see a future where having large numbers of surface vehicles running around doing [intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance missions] and creating communications nodes across vast expanses of ocean? Absolutely. Now the issue is how do we do it and can we do it cost effectively?

“When you get into the lethal end of things, I think we have notions and ideas. We’ve got to go off and experiment and demonstrate and prototype.”

Read Part 2: On Capitol Hill, the US Navy has a credibility problem

Read Part 3: A New Year’s resolution to slow down

David B. Larter was the naval warfare reporter for Defense News.