SAN DIEGO — The sounds of progressive-rock icon Rush crackled through the speakers as the commander of U.S. Pacific Fleet approached the lectern at the West naval conference in California.

Adm. Samuel Paparo, recognizing the tune, smiled as he grabbed the microphone. He then quipped about past lives and “a lot of illegal things” that took place as he came of age in the 1980s.

Times have since changed, and some have found religion in the military, Paparo said. And, much like the times, the demands of a modern-day warrior with a mean, mean stride are constantly evolving.

“We are in the middle of another epochal change,” he said. “And that is the dawn — and I do mean the dawn — of the information age.”

As the U.S. Defense Department prepares for potential confrontations with Russia or China and juggles counterterrorism operations in the Greater Middle East and Africa, it’s emphasizing data: how it’s collected; how it’s shared; and how it can be weaponized. But by some of the department’s own measures, including the 2023 Strategy for Operations in the Information Environment, it is falling behind.

State actors and extremist groups alike have long exploited the information ecosystem in an attempt to distort or degrade U.S. standing. Operating online and below the threshold of armed conflict ducks the consequences of physical battles, where personnel levels, accumulated stockpiles and technology budgets can make all the difference.

The Navy in November published a 14-page document laying out how it plans to get up to speed, arguing neither ship nor torpedo alone will strike the decisive blow in future fights. Rather, it stated, a marriage of traditional munitions and exquisite software will win the day.

The thinking was prominent at the AFCEA- and U.S. Naval Institute-hosted West confab, where Paparo and other leaders spoke, and where some of the world’s largest defense contractors mingled and hawked their wares. Signs promised secure connectivity. Other screens advertised warrens of computerized pipes and tubes through which findings could flow.

“Who competes best in this — who adapts better, who’s better able to combine data, computing power and [artificial intelligence], and who can win the first battle, likely in space, cyber and the information domain — shall prevail,” Paparo said.

Subs and simulation

The U.S. has sought to invigorate its approach to information warfare, a persuasive brew of public outreach, offensive and defensive electronic capabilities, and cyber operations that can confer advantages before, during and after major events. Rapidly deployable teams of information forces that can shape public perceptions are a must, the Defense Department has said, as is a healthy workforce comprising military and civilian experts.

The Navy in 2022 embedded information warfare specialists aboard submarines to study how their expertise may aid underwater operations. That pilot program is now advancing into a second phase, with information professional officers and cryptologic technicians joining two East Coast subs, the Delaware and the California.

Years prior, the service made information warfare commanders fixtures of carrier strike groups.

“This is the first and the most decisive battle,” said Paparo, who previously told Congress that Indo-Pacific Command, his future post, is capable of wielding deception to alter attitudes and behaviors. “The information age will not necessarily replace some of the more timeless elements of naval combat, maneuver and fires, but will in fact augment them.”

RELATED

Tenets of information warfare — situational awareness, assured command and control, and the confluence of intelligence and weaponry — have enabled U.S. forces to bat down overhead threats in the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden while also assisting retaliatory strikes across the Greater Middle East.

Warships Carney, Gravely, Laboon, Mason and Thomas Hudner have destroyed more than 70 drones and seven cruise missiles since the start of the Israel-Hamas war in October. Prior knowledge regarding the armaments and installations of Iran and the Houthi rebel group in Yemen has made it easier, albeit dangerous.

Information warfare “underpins every single warfare mission in the Navy today,” Elizabeth Nashold, the deputy at Naval Information Forces Command, said at the West conference. “You name that mission, and there’s an IW component to it.”

“USS Carney was ready on Day 1,” she added. “We are in an information age, and we are seeing proliferating technologies, and we have to keep up.”

Ensuring sailors are well-versed in information warfare has proved tricky, as the sensitivity of tools employed clashes with the always-alert eyes and ears of Russia and China. The U.S. Navy has for years wanted to flesh out its simulation and gaming environments to bridge the gap, but has run into both engineering and bureaucratic walls.

“A lot of our IW capabilities are at a higher classification level than what we see in the current live, virtual and constructive operating environment,” Nashold said. “The other challenge is really just getting all the different IW capabilities into LVC.”

The Navy plans to introduce 20 information warfare systems into its live, virtual and constructive environments. The first few — focused on cryptology, meteorology and oceanography — will be uploaded in the fourth quarter of fiscal 2025, according to Nashold. Other information warfare disciplines include communications, cryptology and electronic warfare, or the ability to use the electromagnetic spectrum to sense, defend and communicate.

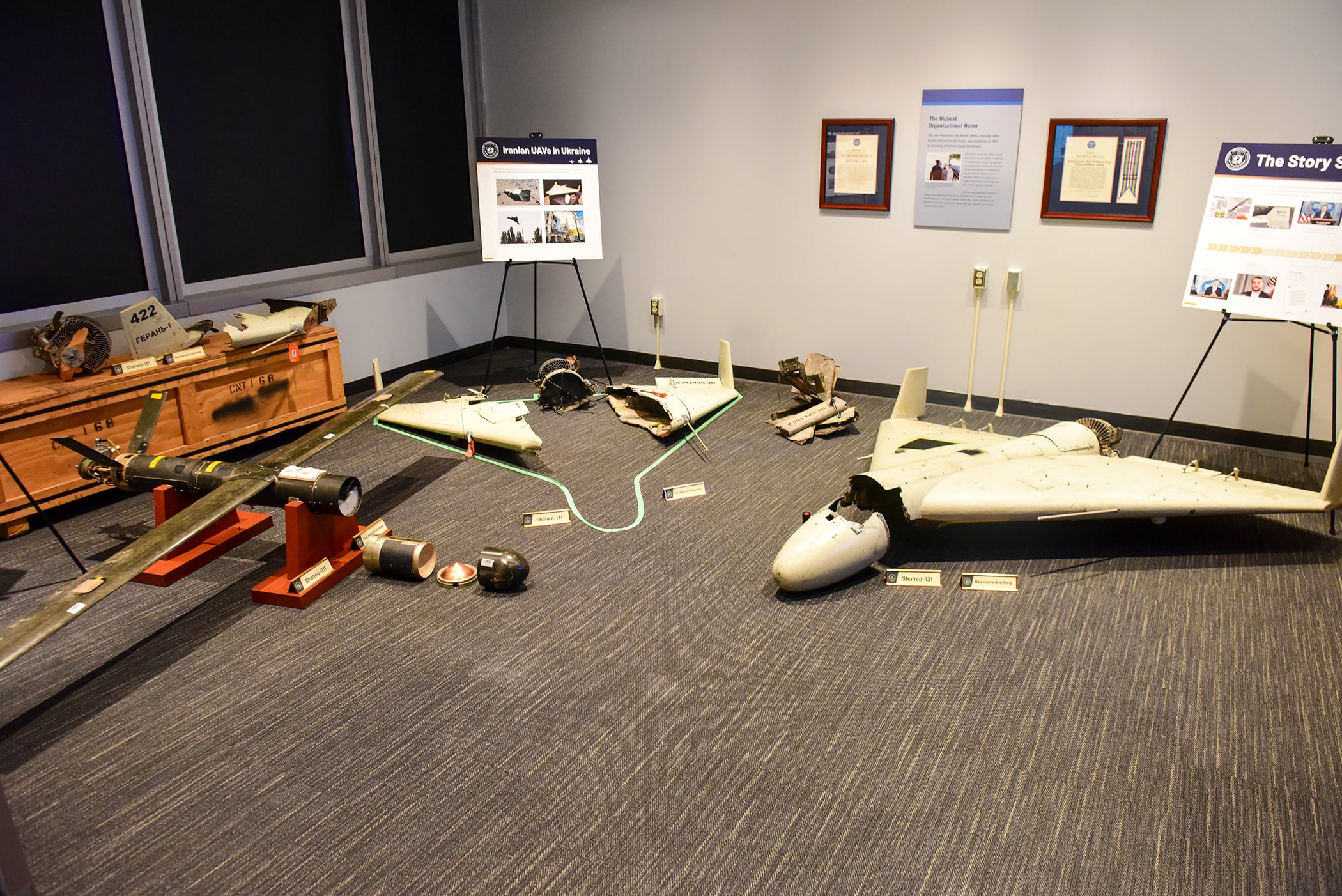

Image 1 of 12

Additionally, the service is eyeing ashore training facilities in locations where sailors and sea power are concentrated: California, Virginia and Japan.

“They’re basically going to be places where sailors can come and actually train to execute those capabilities,” Nashold said. “Once we get into the environment, our IW sailors can run all of our IW capabilities concurrently, and they can actually innovate and iterate and practice over and over again.”

Safe and secure

The Navy’s inaugural cyber strategy, published late last year, underlined the value of virtual weaponry. Non-kinetic effects — capable of wreaking havoc on electronic guts and subsystems — will prove increasingly potent as militaries adopt interlinked databases and units.

In the U.S., the vision of connecting once-disparate forces across land, air, sea, space and cyberspace is known as Combined Joint All-Domain Command and Control. In China, the weaving of command and control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance to quickly coordinate firepower is known as Multi-Domain Precision Warfare.

The former considers the latter a top-tier national security hazard. Defense Department documents describe Beijing as determined to reorient international power in its favor. Such ambitions can take many forms, economic and narrative among them.

“We all know information is combat power, and really the next fight is an information-domain fight just as much as a physical, kinetic fight,” Jane Rathbun, the Navy’s chief information officer, said at West. “We want to make sure that we provide our sailors and Marines with trustworthy, secure information at the time of need.”

Shuttling intel back-and-forth runs the risk of interception or poisoning. Tampering could go undetected, as well, exposing troops to unnecessary risks down the line.

RELATED

“The golden rule in the information superiority vision is the right data, the right place, the right time, securely. And the ‘securely’ piece is critically important,” Rathbun said.

The service’s cyber blueprint identifies critical infrastructure — such as bases, far-flung logistics nodes, and food and water supply chains — as a soft underbelly in need of thicker insulation.

The Five Eyes intelligence-sharing alliance, made up of Australia, Canada, New Zealand, the U.K. and the U.S., warned in May a Chinese espionage group slipped past digital defenses in Guam and other locations. Microsoft had detected the breach and attributed it to a group known as Volt Typhoon. A successful cyberattack on infrastructure in Guam or other Indo-Pacific footholds could cripple U.S. military capabilities in the area.

“Volt Typhoon is out there, it’s real,” Scott St. Pierre, who serves as the Navy’s principal cyber adviser, said at West.

“We’re in battle today,” he added. “Information is power.”

Colin Demarest was a reporter at C4ISRNET, where he covered military networks, cyber and IT. Colin had previously covered the Department of Energy and its National Nuclear Security Administration — namely Cold War cleanup and nuclear weapons development — for a daily newspaper in South Carolina. Colin is also an award-winning photographer.