WASHINGTON — To avoid past mistakes that have all but crippled the Army’s ability to procure new equipment, the service should ensure its top modernization priorities are aligned with its emerging warfighting doctrine, which could mean rearranging some of its top efforts, conservative think tank The Heritage Foundation is arguing in a new report.

The assessment comes at a time when the Army is preparing to release a new modernization strategy in short order.

“From 2002 to 2014, for a variety of reasons, nearly every major modernization program was terminated,” the report’s author Thomas Spoehr writes. Spoehr is the director of the Center of National Defense at Heritage. His former Army career was partly spent helping to develop the service’s future year financial plans.

RELATED

Spoehr acknowledges that with the advent of a new four-star command — Army Futures Command — the programs envisioned to modernize the Army “are well-conceived,” but urges the services to look through a lens of how its priorities measure up in Multi-Domain Operations — a concept under development that will grow into its key warfighting doctrine.

RELATED

Spoehr also warns the Army’s leaders that there needs to be a balance “of the lure of technology with the necessity" to buy new equipment.

The service is steadfastly marching down a path to modernize and develop its capability in Long-Range Precision Fires, Next-Generation Combat Vehicle, Future Vertical Lift, the network, air-and-missile defense and soldier lethality, in order of importance.

But Spoehr is proposing to drop NGCV and FVL to the bottom of the list because they would serve less effective roles when carrying out operations in an environment where territory is well defended against enemies like Russia and China.

RELATED

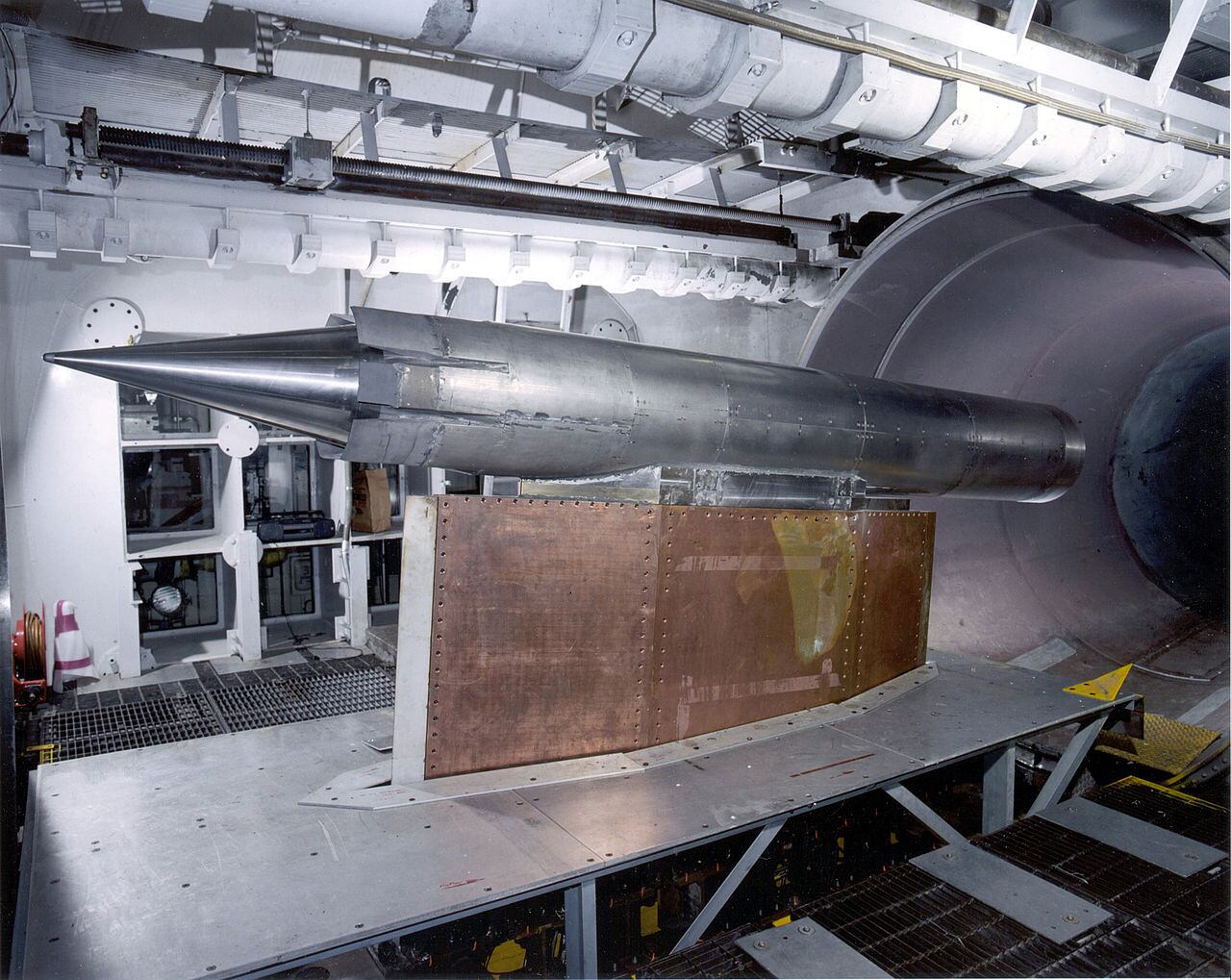

“The need for long-range precision fires and a precision-strike missile with a range of 310 km, for example, is grounded in the need to strip away Russian surface-to-air missile batteries and gain access,” Spoehr writes. “The linkages of other programs and initiatives are not as obvious and would benefit from an Army effort to make the connections either more explicit or reconsider requirements.”

Spoehr points out that it’s not clear, for example, how a Future Long-Range Assault Aircraft and a Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft “might survive against near-peer sophisticated integrated air defense capabilities like the Russian’s capable Pantsir-S1 SA-22 system.

“Even if the aircraft’s speed is doubled or tripled, it will not outrun the Pantsir’s 9M335 missile,” he writes.

“Nowhere in the MDO concept is a compelling case made for the use of Army aviation, combined with a relative youth of Army aviation fleets,” he adds.

Instead, Spoehr said, the priorities “should be based on an evaluation of current versus required capabilities, assessed against the capability’s overall criticality to success, and all tied to a future aim point-2030, by a force employing MDO doctrine.”

This means, he argues, that the Army’s network should be prioritized just below LRPF, followed by AMD and soldier lethality. Ranked at number five and six would be NGCV and FVL, respectively.

According to Spoehr, “nothing has come forward to suggest that there is a technological advancement that will make a next generation of combat vehicles significantly better.”

Additionally, the Army should not try to force the key requirement of making its Bradley Infantry Fighting Vehicle replacement — the Optionally Manned Fighting Vehicle — robotically operated or autonomous until the network matures to support the capability, the report notes.

RELATED

The Army needs a network “that is simple, reliable and less fragile than its current systems,” Spoehr says. “These capabilities may need to come at the expense of capacity,” which the Army appears to be doing, he notes.

Spoehr also suggests that the Army invest less in hypersonic offensive capability and more in defensive capability.

RELATED

But ensuring effective modernization of the force and avoiding past failures is just as much a management challenge as it is overcoming technological and cost hurdles.

One of the phenomena Spoehr observed during his time serving in the military, particularly at the Pentagon, is what he calls “groupthink,” where those who spend time together begin to think alike and make decisions without those around them questioning actions. Additionally, subordinates tend to avoid disagreeing with those in charge.

Groupthink has been the culprit when it comes to major failure in development and acquisition programs in the past, so the Army should “zealously promote critical thinking and avoid groupthink,” Spoehr writes. The service should “promote a free and open dialogue in journals and forums” and “exercise caution when senior leaders endorse specific system attributes or requirements to avoid closing down discussion.”

The report acknowledges that the Army “is making a concerted effort to change to meet the future,” such as standing up AFC and aligning its future doctrine with materiel solutions more closely.

It’s important the Army keep sight of what it’s actually trying to do with its future capability, the report warns. “Rather than seeking to match and exceed each of our adversary’s investments, the Army must focus on enabling its own operational concepts and seeking answers to tough operational and tactical problems,” it states.

Elsewhere in the overarching analysis, Spoehr recommends growing the force, as well ensuring its effective modernization to include roughly 50 Brigade Combat Teams and an end-strength of at least 540,000 active soldiers.

He suggests reducing investment in infantry brigade combat teams in favor of armored BCTs, but also to keep capability to fight in a counter-insurgency environment as well, such as keeping the Security Force Assistance Brigades. The third such formation is preparing to deploy to Afghanistan.

RELATED

The Army also needs to grow faster and must find ways to resolve recent problems with recruiting, Spoehr said, recommending that the service grow at a rate faster than 2,000 regular Army soldiers per year.

And force allocation should also be reconsidered, Spoehr argues, recommending that the Army should create a new field headquarters in Europe and, when appropriate, do so in the Indo-Pacific.

Overall, “the task for the Army is no less than to develop a force capable of deterring and defeating aggression by China and Russia, while also remaining prepared to deal with other regional adversaries (Iraq and North Korea), violent extremist organizations, and other unforeseen challenges,” Spoehr said.

What’s hard for the Army is that it lacks “the certainty of a single principal competitor” — the Soviet Union in 1980s, during the last buildup, for example, he noted.

Because of the complicated global environment, Spoehr advocates for the Army to shift from thinking about a 20-year lead time for new, transformative capabilities and instead take a constant iterative and evolutionary approach to building the force. Under AFC, the Army is attempting to do just that.

The Army can’t wait “until the future is clear before acting,” he adds. “When dealing with a 1-million-person organization, equipping, training, and leader development typically takes at least a decade to make any substantive change,” Spoehr said. “The Army must therefore make bets now to remain a preeminent land power.”

Jen Judson is an award-winning journalist covering land warfare for Defense News. She has also worked for Politico and Inside Defense. She holds a Master of Science degree in journalism from Boston University and a Bachelor of Arts degree from Kenyon College.