While the collapse of the Donald Trump-Kim Jung Un summit should cause the president to reconsider how to prepare for head of state summits, it should not alter the Trump administration’s strategic objective of complete and permanent denuclearization of North Korea for several important reasons.

The leverage of sanctions is greatest now. Since the end of the Cold War and the rise of the global economy, we have entered a new era of arms control/non-proliferation policy where the leverage to stop these programs and reverse them comes from multilateral sanctions. Multilateral sanctions have reached an important apex with North Korea, with increased Chinese support for the Trump administration’s sanctions policy in the UN Security Council and with significant success in encouraging countries across the globe to diplomatically isolate North Korea.

Arms control dependent on the persuasion of sanctions limits the utility of phased negotiations. As sanctions weaken in response to step by step moves, sanctions pressure decreases just as the slow burn approach to negotiations has to deal with the final phases of complete denuclearization. A sanctions dependent arms control policy sharply limits the effectiveness of step by step negotiations or time-bound constraints, one of the major concerns with the time bound limits of the Iran agreement.

Furthermore, the nuclear genie is out of the North Korean bottle and a freeze does not diminish that threat. North Korea is a nuclear state with both medium range and long-range ballistic missiles and an estimated 10-60 warhead capability. The only remaining question is whether they can reliably put a warhead on a missile — a capability that North Korea says it already has. Freezing missile tests and nuclear weapons tests at this point does not limit North Korean capabilities, which currently threaten our allies, our assets and personnel in the region, and the U.S. homeland.

RELATED

Consequently, a freeze also does not deserve to be rewarded with sanctions relief or diplomatic recognition. The U.S. unilaterally removed all of its tactical nuclear weapons from South Korea during the George H.W. Bush administration. North Korea is the only non-member of the Non-Proliferation Treaty in the region and among only four outliers to the Non-Proliferation Treaty regime globally. North Korea is the country that is introducing nuclear weapons onto the peninsula, violating its own past and now reiterated commitment for a nuclear free Korean peninsula.

The alternative to complete denuclearization is not simply war, if the goal fails. Along with defense and deterrence measures, the U.S. can continue its policy to pressure and isolate North Korea economically and diplomatically. It can continue to clamp down on its proliferation and other black market activities, which are important sources of hard currency and, thus, denying Kim Jung Un of his equally important goal of developing North Korea economically.

North Korea is also not Libya, Iraq or Ukraine. North Korea has publicly stated that their pursuit of nuclear weapons is to keep the Kim regime from the fate of others: Qaddafi, who gave up nuclear weapons only to be killed in an allied attack; Saddam Hussein whom the North Koreans believe was successfully invaded because he did not have nuclear weapons; or Ukraine who gave back nuclear weapons to Russia for promises of sovereignty only to have that promise to collapse with the Russian invasion.

North Korea is in a very different situation and, in fact, can be secure without nuclear weapons. It has superpowers on its borders that can provide security guarantees and can offer a nuclear umbrella to counter U.S. extended deterrence with South Korea. North Korea has the potential to leverage a relationship with both China and Russia as a deterrent against U.S. interference. One of China’s principal objectives is to avert a regime collapse in North Korea and a refugee influx on its border. Russia, North Korea’s original mentor before the collapse of the Soviet Union, has also demonstrated its interests in working with the Kim Jung Un regime. These potential security guarantees plus the economic development incentives that these superpowers plus South Korea, Japan and the U.S. can provide, make complete denuclearization not an unreasonable objective.

While reversing a nuclear weapons program is very difficult, it is not impossible. The U.S. and the global community have achieved this goal in the past with several countries under the Non-Proliferation Treaty regime over the years. Anything short of complete denuclearization does not solve the current security threats of a nuclear North Korea to the U.S. or our regional allies.

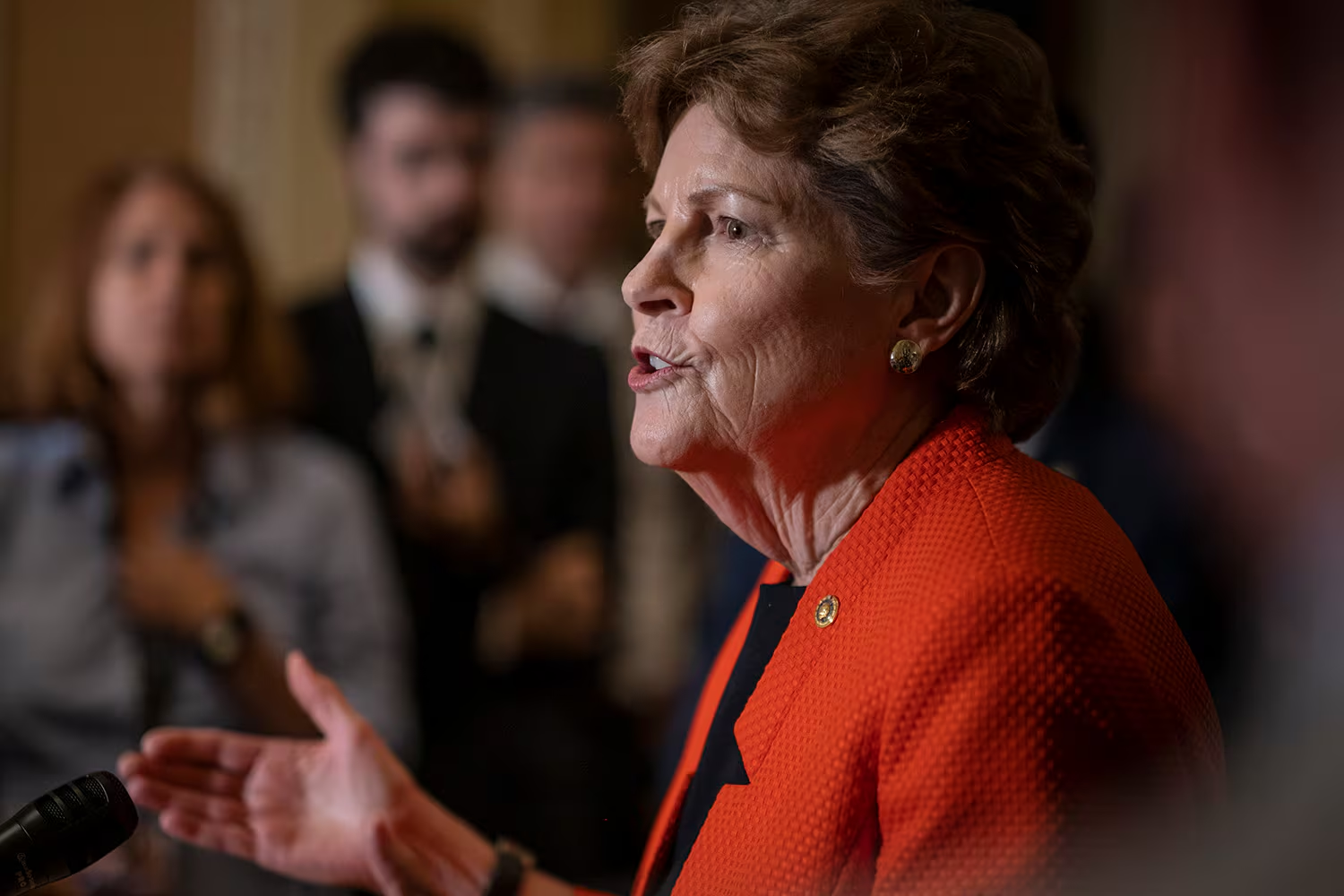

Lori Esposito Murray is an adjunct senior fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations.