The United States’ long-standing commitment to maintaining Israel’s qualitative military edge, or QME, forms a central pillar of Israel’s security strategy.

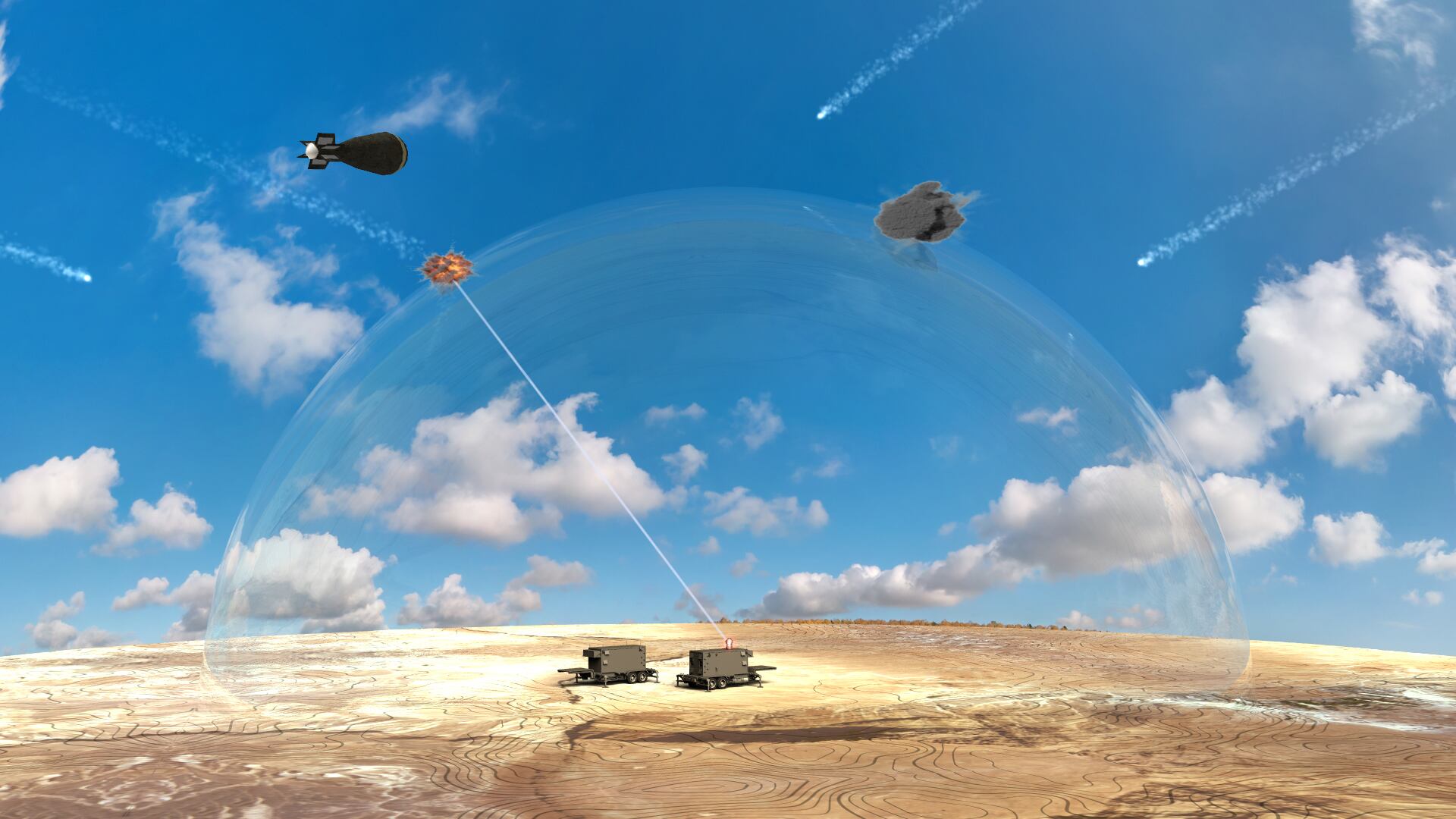

The U.S. commitment reflects the bipartisan support for Israel that has been expressed by all recent U.S. administrations and Capitol Hill. It encompasses multiyear military financial assistance made available to Israel for procuring weapons systems, as part of the U.S.-Israel Memorandum of Understanding; the joint development and production of missile defense systems; the sharing of intelligence information and missile alerts; and the holding of joint military exercises. American support also takes the form of pre-positioning U.S. military equipment on Israeli territory.

In order to ensure that this cooperation remains sturdy into the foreseeable future, both Israel and the U.S. will need to address several emerging challenges. Chief among them is Iran, whose hegemonic ambition in the Middle East is sparking a broader arms race between the Iranian-led Shiite axis and Arab Sunni states. This arms race jeopardizes Israel’s QME.

An additional challenge is the sheer volume of defense deals undertaken in the Middle East since the beginning of the 21st century, totaling hundreds of billions of dollars.

A third factor in considering threats to Israel’s QME is the fact that while the U.S. remains the main supplier of weapons systems in the region, European, Russian and even Chinese defense industries are becoming more prominent suppliers to Middle Eastern states.

The systems sold by these counties range from items that the U.S. has refused to sell (sometimes due to Israeli objections), such as armed drones, ballistic missiles, main battle tanks, armored personnel carriers, air defense batteries and more.

RELATED

In light of the above, there are Middle Eastern states — the Gulf petrodollar nations — with deep pockets that could easily afford to buy significant maritime and/or airborne fleets that are out of Israel’s economic reach. The higher the cost of platforms, the more the trend is pronounced.

At the same time, the Middle East is undergoing rapid changes, with three Arab countries — two of them Gulf states — signing historic normalization treaties with Israel, creating a different environment when compared to just a decade ago.

Israel’s core strategy of enhancing, strengthening and deepening its ties with Gulf states relies on a common mutual interest based on a view of Iran as a strategic enemy. With both Israel and the Gulf states facing a similar threat from Iran and its proxies, it remains unclear how wise a policy it is to object to Gulf countries procuring modern weapons systems from the U.S.

Blocking such procurements could push the United Arab Emirates to purchase Russia’s Su-57 stealth fighter jet instead of the U.S. F-35 aircraft, and it is not clear how such a scenario would better serve the mutual interests of the U.S. and Israel. The question of whether such an attitude would cause harm to the newly tightened Israeli-Gulf strategic relationship remains relevant.

No policy is free from built-in risks, and it is necessary for Israel to identify these in the pursuit of its QME in the new geopolitical environment, and to manage them appropriately.

Two of the most disturbing risks are long-term regime instability and the slippery slope potential of other countries achieving advanced defense technology.

In terms of regional instability, regional political history has witnessed multiple regime changes in recent years, and governments that are pragmatic today could become hostile tomorrow. Well-known examples include the Muslim Brotherhood’s takeover of Egypt, or the conversion of Turkey from an ally of Israel to a bitter opponent. Iran itself underwent the most drastic of changes, going from a close partner to the U.S. and Israel until 1979, when it became a sworn adversary after the Islamic Revolution.

The slippery slope risk means if the U.S. were to sell, with Israel’s approval, state-of-the-art technologies to country A, preventing country B from acquiring the same technology or platform would become highly complex and difficult.

In order to navigate these risks with minimum negative impacts to Israel’s qualitative military edge, establishing win-win strategies is an advisable path. This can include technological differentiation, which is based on the idea that not all platforms are the same and that the U.S. can keep some of its naval and airborne platform software packages to itself. Opening new technological routes for upgrading Israeli-American mutual cooperation, and increasing the volume and diversity of American pre-positioning of military equipment in Israel, would also further such strategies, as would deepening cooperation in missile defense; intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance; and cooperation in space.

With Israel’s resources limited in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, an additional route to promoting its QME is through a U.S. government commercial loan, guaranteed against the funds provided by the 10-year Memorandum of Understanding.

At the same time, since Israel is also a defense technology and weapons supplier in its own right, bilateral cooperation between the U.S. and Israel on arms sales to the region could pave the way forward to a trilateral and more healthy relationship: the U.S., the Gulf and Israel.

Ultimately, American and Israeli policies for maintaining Israel’s QME, in place since the 1960s, are due for an update. Tectonic changes in the region require fresh policies from both Washington and Jerusalem. An updated and balanced bilateral policy can enable Israel’s new peace partners to benefit from the diplomatic process they have entered, while minimizing erosion of Israel’s QME.

Yair Ramati is a publishing expert at the MirYam Institute. He is a former director for the development, production and delivery of missile defense systems with Israel’s Defense Ministry.