The Pentagon has a problem. The Defense Department report last month on the Chinese military makes clear that Beijing is sprinting to develop the means it would need to conquer Taiwan. Unfortunately, many of the weapons Washington is sending to help Taipei deter or defeat that aggression are not scheduled to arrive anytime soon.

The Harpoon coastal defense system and the missiles it fires are a good example. The Defense Security Cooperation Agency announced in October 2020 the decision to approve a $2.37 billion sale to Taiwan of 100 of the delivery systems as well as 400 Harpoon Block II surface-launched missiles. These systems would provide Taiwan a “highly reliable and effective system to counter or deter maritime aggressions, coastal blockades, and amphibious assaults,” DSCA noted.

Unfortunately, due to insufficient production capacity, the lack of a contract between the U.S. Navy and Taiwan, and unacceptable continued delays associated with foreign military sales, the Harpoon shipment to Taiwan will not be complete until long after 2027.

Many worry that the People’s Republic of China could launch military aggression against Taiwan before then. The good news is that there are ways to expedite both the delivery of the system and the Harpoon missiles.

RELATED

Harpoons are capable of hitting moving targets at sea and fixed targets on land with its approximately 500-pound warhead out to a range of at least 124 kilometers (77 miles), which would cover much of the Taiwan Strait. That is a vital capability for Taiwan, especially considering Beijing’s growing naval capabilities.

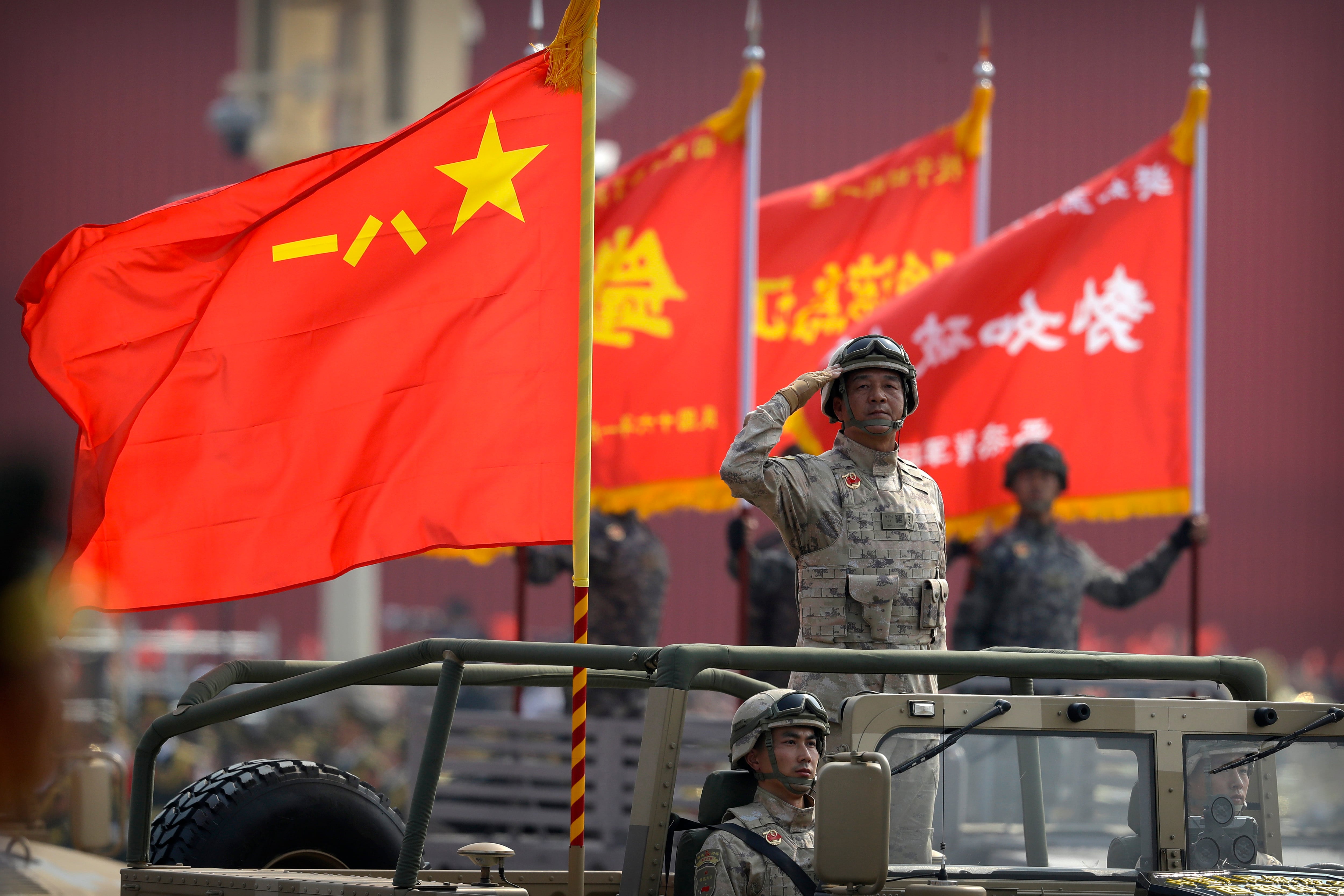

China boasts the largest navy in the world (approximately 340 ships and submarines) and is “the top ship-producing nation in the world by tonnage,” as the Pentagon’s China military power report notes, and “the [People’s Republic of China] is increasing its shipbuilding capacity and capability for all naval classes: submarines, warships, and auxiliary and amphibious ships.”

To ensure it could employ these capabilities effectively, Beijing is devoting significant amounts of its maritime training on island-capture scenarios. In 2021, the People’s Liberation Army “conducted more than 20 naval exercises with an island-capture element, greatly exceeding the 13 observed in 2020,” according to the report.

So what can be done to get the Harpoon systems to Taiwan sooner?

The Pentagon and Taiwan’s Ministry of Defense should start by using a “MacGyver”-type approach, not unlike the method used to get a Harpoon capability to Ukraine quickly. While such an effort for Taiwan would need to be conducted on a larger and more sustainable scale, using existing components can expedite delivery of initial capabilities for Taiwan, too.

The Pentagon and Taiwan’s MoD should work with Boeing, the manufacturer of the Harpoon, to design and field this system rapidly — something that can realistically be done by early 2024 and serve as a bridge to the 100 newly fabricated launcher systems requested by Taiwan.

This gap filler can be accomplished by building a relocatable ground-launch platform from existing U.S. inventories of Harpoon missile-launch support structures, Harpoon Ship Command-Launch Control Systems, ground platforms (essentially a steel plate), power generators, and communications systems providing voice and a data link to provide targeting data.

If Taiwan wants a more mobile system, it could work with the producer to mount a variant on an existing Heavy Expanded Mobility Tactical Truck instead of the steel plate. The launch support structures and Harpoon Ship Command-Launch Control Systems would be drawn from those taken off decommissioned U.S. Navy ships. The communications and data link could come from existing Taiwan systems. The generators and trucks can come from either country’s inventories. The missiles should come from the several hundred older missiles in the Navy’s inventory that are under consideration for demilitarization or destruction.

A prime contractor would need to pull these pieces and parts together — much as was done for Ukraine in a few short months — or in the standard episode of any “MacGyver” TV series.

A short fuse-procurement effort should include the purchase of four of the ground launchers, four of the truck-based launchers, and 64 missiles (each launcher holds four missiles, so eight launchers would need 32 missiles and a reload would require a further 32 missiles). If it becomes clear that the existing new construction procurement is delayed past 2026, an additional 64 missiles should be considered.

Delivering on the necessary timelines would require DSCA, Taiwan’s MoD, the U.S. Navy and Boeing to all be significantly more efficient and driven than we have seen in almost every case outside Ukraine over the past decade. The cost estimates (Boeing), the price agreement (Taiwan’s MoD), the paperwork (U.S. Navy), and the drawdown from inventory (United States and Taiwan) should all be fast-tracked within each organization. Strong congressional support and oversight will be critical throughout the process.

Simultaneously, Congress should work with the Pentagon to dramatically expand Boeing’s Harpoon missile production capacity. Such an order in the first quarter of fiscal 2024 could enable the United States to deliver the 100 Harpoon launchers and all 400 missiles by 2027 — significantly earlier than currently anticipated and potentially in time to help deter aggression.

Thankfully, the text of the fiscal 2023 National Defense Authorization Act released Wednesday authorizes the Pentagon to enter into a multiyear agreement for 2,600 Harpoon missiles. There is also money authorized to expand the associated defense-industrial base. If congressional appropriators support those authorizations with the necessary funding, it could provide a running start.

Meanwhile, Japan, South Korea and Australia possess hundreds of Harpoon missiles as well, and Washington should explore whether these countries might be willing to transfer — directly or indirectly — some of their Harpoon missiles to Taiwan in return for U.S. commitments of future capabilities.

The horrible events in Ukraine since February offer a painful reminder regarding the costs of procrastination and an unwillingness to provide beleaguered democracies the help they need before a potential invasion begins.

Washington demonstrates a world-class capability when it comes to issuing press releases announcing new arms sales to Taiwan. Now it is time to demonstrate world-class capability in delivering the combat capability.

War in the Taiwan Strait would be a disaster, but it is an avoidable one. Washington can decrease the likelihood of such a conflict by moving heaven and earth now to get Taiwan the Harpoon systems and missiles it needs as soon as possible, even if it takes some “MacGyver” magic.

Retired U.S. Navy Rear Adm. Mark Montgomery is a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies and the senior director of its Center on Cyber and Technology Innovation. Bradley Bowman serves as senior director of the Center on Military and Political Power at FDD, where Ryan Brobst is a research analyst.