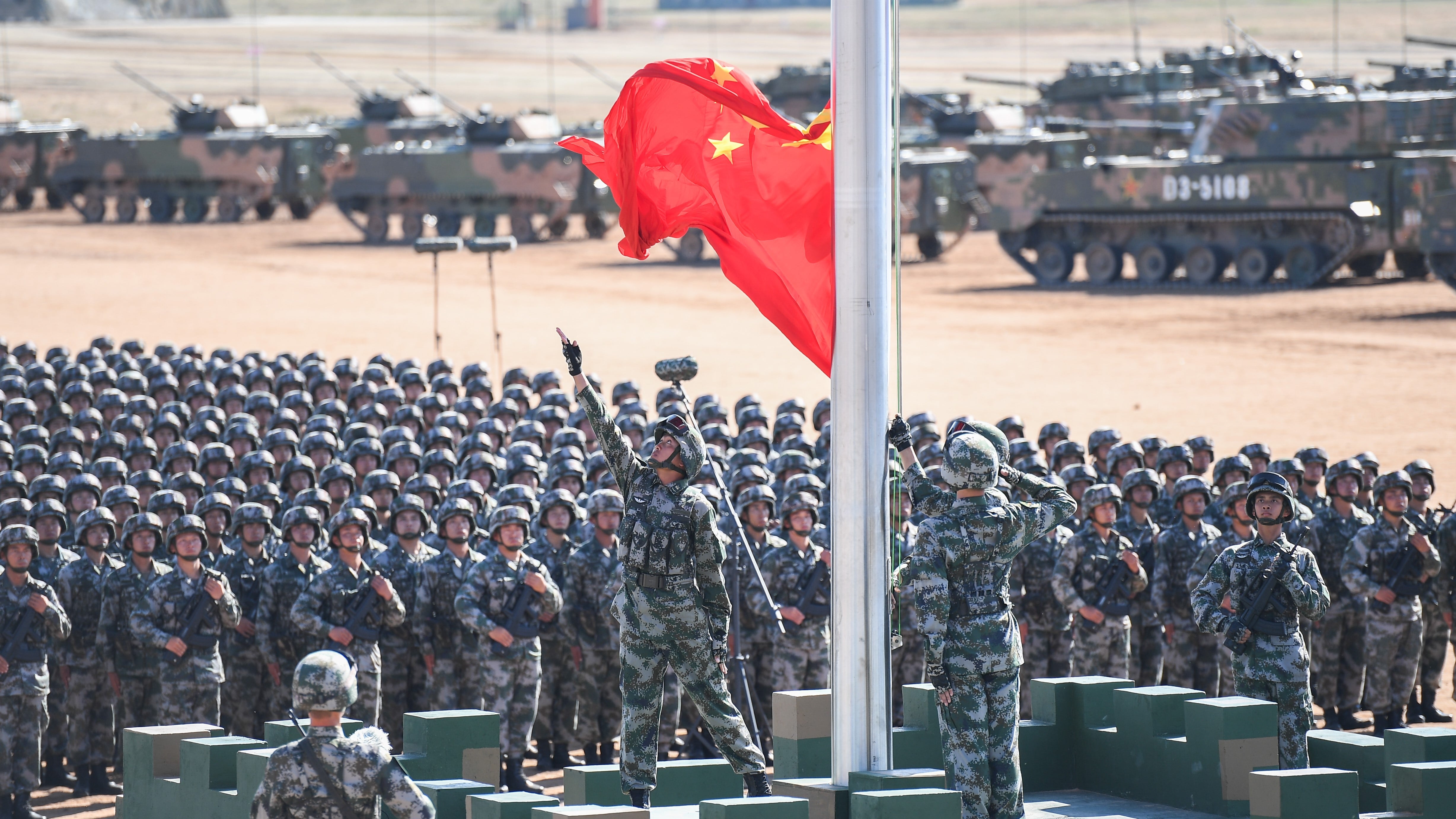

WASHINGTON — For several years, Pentagon officials have been sounding the alarm about China’s growing military abilities, with a particular focus on how Beijing has closed the technology gap between the two nations.

But when discussing that, officials and experts often also note that the U.S. remains ahead in a key capability: training and doctrine for its war fighters.

It’s the way American soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines can think on the fly and make decisions under pressure. It’s the ability for the branches to coordinate efforts across a battlefield, region or on a global scale.

“The greatest advantage that the US has at the moment over the PLA (the People’s Liberation Army) is that the U.S. has been working on doctrine, training, professionalization for a lot longer than the PLA, with actual experience to back it up,” said Meia Nouwens, a Chinese military expert with the International Institute for Strategic Studies.

RELATED

But PLA leadership is aware of its shortcomings, and Chinese officials have previously been open about the need to improve training. For instance, a Feb. 5 article published in the South China Morning Post quoted a retired Chinese naval officer as saying: “Some people hold the view that our military planes are more advanced than others. But if we look at the level of training of our forces ... we are not at the same level [as others] yet.”

Chinese President Xi Jinping has launched a series of military reforms to try and force more joint operations and planning — reforms that could lead to the PLA becoming a more formidable force.

That assessment is shared, at least in part, by the U.S. Defense Intelligence Agency, which in January released a new report on China’s military power.

A senior DIA official, briefing reporters, acknowledged that China is dramatically closing the gap when it comes to technology, but noted “there is more than just technology involved; there’s experience, there’s experience, there is command structure, there is training, there is proficiency.”

“I think there will be significant growing pains, but they seem to have chosen a blueprint for how they want to move forward to be what they consider an advanced military,” the DIA official said. “But it'll take some time.”

Just how much time? That’s hard to pin down, according to analysts. But the consensus seems to be that the PLA will have reformed itself sometime in the next two decades into a force capable of joint operations.

“They've been talking about joint operations for a long time, but some of is it just now sort of being implemented. And it will take a while for them to be able to work these services together, to be able to work these joint theaters and to be able to deal with a large, complex operation,” the official added. “So I think in a lot of ways, they have a lot that they need to do.”

But technology and money matter in the equation. Per IISS figures, China’s official defense budget grew in real terms by 10 percent on average, year over year between 1998 and 2018. Much of that was invested in the PLA Navy and the PLA Air Force, as well as toward innovations in space, cyber and cutting-edge capabilities like artificial intelligence.

That’s something for the U.S. to watch closely, said Nouwens.

“The bottom line is that no matter where you think the PLA are outmatched, the most important thing to realize is that the PLA and its leadership are fully aware of where they need to improve,” she said. “And they’re throwing massive resources at fixing their weaknesses.”

Experience still counts

PLA leadership isn’t shy about watching and learning from the U.S. military, and China watchers say Beijing tracks how the U.S. military operates. But Roy Kamphausen, senior vice president for research with the National Bureau of Asian Research, says China may never be able to fully close that gap without getting directly involved in conflict.

“This is an area of great advantage for the United States. It’s not that we have a unique way to prosecute war that is a secret from the rest of the world and therefore — irrespective of system capabilities or any other independent variable — we would win because we have great doctrine. It’s that we have doctrine that is actually being tested in combat,” Kamphausen said.

“I don’t think we can overstate how critical a factor this is. I’m not arguing that we ought to fight wars just because it gives us an advantage of war fighting, but no other military achieves a comparable set of effects in leveraging effective command and control to implement doctrine using the advanced capabilities it has and making the most of the highly trained set personnel.”

While agreeing China has fallen behind because of a lack of external conflicts since the 1970s, Nouwens warned it “would be naive and wrong to assume that just because the Chinese haven’t fought a war, they’re not learning.”

“The PLA and its leadership keenly watch for lessons learned from other countries’ wars — and so, too, are learning from U.S. experiences in the Middle East, for example. Furthermore, joint exercises between the PLA and other militaries, such as the Vostok exercises with Russia, are also used to learn and gain experience during peacetime.”

She added that in drills, high-ranking officers are rewarded for taking risks, and there is anecdotal evidence that low-ranking officers are being given greater decision-making rights — potentially eroding that aspect of America’s advantage.

So would China be willing to get involved in a conflict in the next two decades to test its doctrine?

Neither Nouwens nor Kamphausen see China seeking out a major power conflict in the near term. But there may be options for something smaller in China’s backyard, whether over a long-simmering conflict with Japan over the Senkaku Islands, or with the long-sought apple of Beijing’s eye: Taiwan.

The DIA official said that while China could devastate Taiwan today with ground-based cruise missiles, the PLA appears unconvinced China’s armed forces are up for an invasion and occupation. However, the official did say China is approaching the point where officers are more willing to consider an invasion — a major milestone for the PLA.

Kamphausen said he was “quite taken” by that DIA statement, noting it is a change in the long-standing American view about the PLA’s internal judgments on readiness. But still, he predicted, China will try to avoid any direct conflict with the U.S. for some time, even if it is in Beijing’s regional sphere of influence.

“In specific scenarios, usually closer in to China, they can imagine a context in which the PLA Navy and ground-based or land-based missile systems could create a strike effect which could devastate or defeat a U.S. naval task group, in a specific set of limited circumstances,” he said. "But this begs the question as to what comes next. The PLA is really good at conducting pre-conflict ‘strategic assessment of the situation,’ and they will surely judge that the U.S. would respond in a very robust way to an initial PLA strike.

“As a consequence, I’m not of the view that they are gunning for early war with the U.S. I don’t see how it supports their broader developmental goals because the stakes are so high for the [Communist] Party that to pick a fight with the U.S. that they could well lose puts the regime at risk."

Added Nouwens: “China’s goal of regional power is set for 2035, while a more global role is envisioned by 2049. Other than a potential Taiwan scenario, there is no real pressing need for the Chinese to be a military peer competitor with the U.S. just yet.”

Aaron Mehta was deputy editor and senior Pentagon correspondent for Defense News, covering policy, strategy and acquisition at the highest levels of the Defense Department and its international partners.