PARIS — France has launched the first of three identical military imaging satellites, which, when they reach full operational capability at the end of 2021, will replace the aging Helios system and provide 800 very high-resolution black and white, color, and infrared images per day for European military and civilian intelligence agencies.

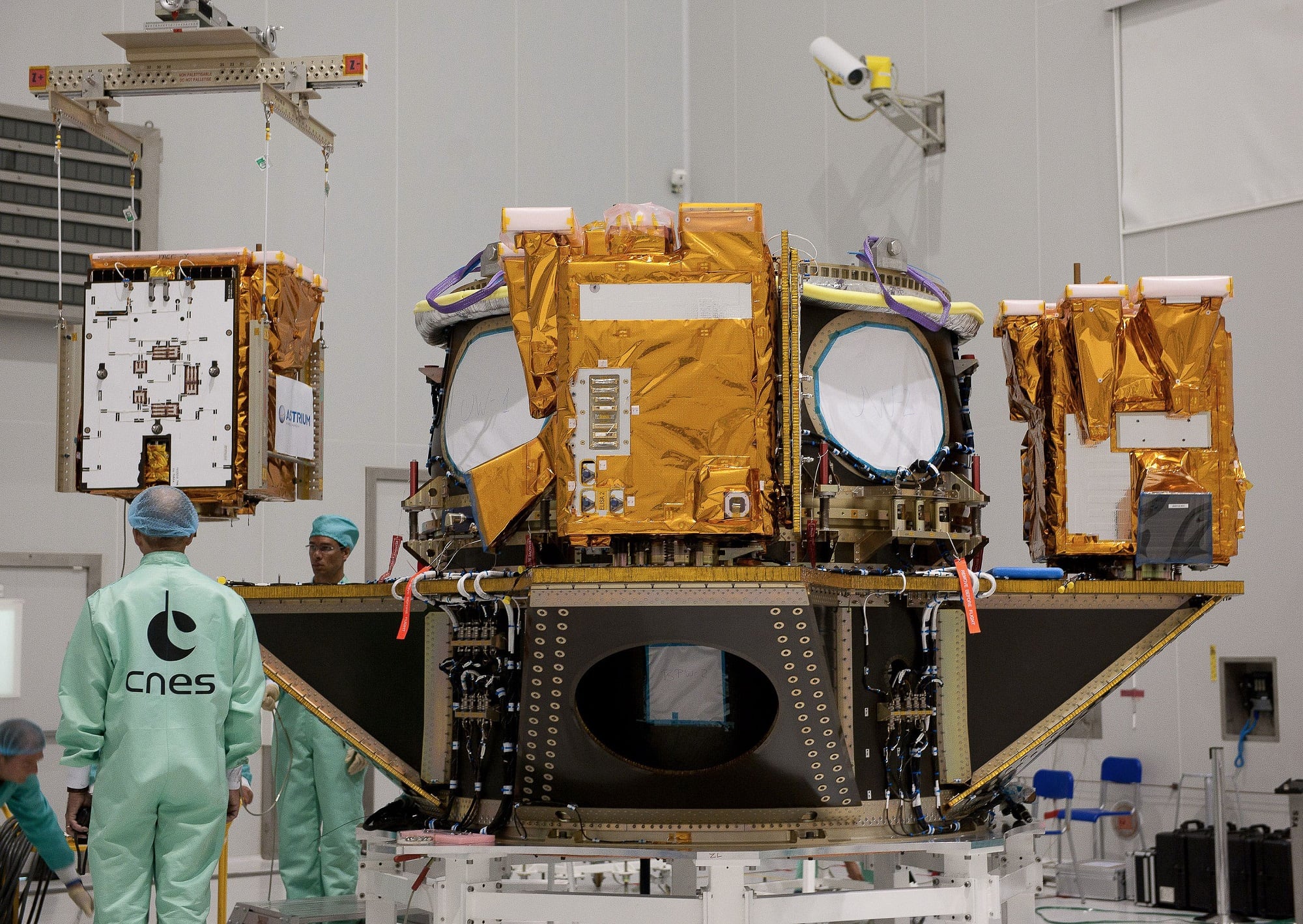

CSO-1 (Composante Spatiale Optique, or Optical Space Component), made by Airbus Defence and Space as well as Thales Alenia Space, was launched by a Soyuz rocket on Dec. 19 from the European space base in Kourou, French Guiana, 24 hours late because of high-altitude winds.

This 3.5-ton satellite and its sister CSO-3 — to be launched by the new Ariane 6 European rocket in October 2021 — are very high-resolution observation satellites that orbit 800 kilometers above Earth. The CSO-2, an extremely high-resolution identification satellite — to be launched by a Soyuz rocket in May 2020 — will orbit Earth at an altitude of 480 kilometers. At this altitude, the satellite will need to automatically reset its orbit twice a day to compensate for the planet’s gravitational pull.

Completing the €1.485 million (U.S. $1.688 million) CSO system are the SSM ground mission base in Toulouse, southwest France (operated by the CNES French government space agency) and the SSU ground user center at the CMOS Military Center for Observation by Satellite at the 1/92 Bourgogne French Air Force Base in Creil, just north of Paris.

CMOS will receive and prioritize all image requests from France, but also from CSO partners Belgium, Germany and Sweden (Italy will sign up in early 2019).

RELATED

The center also currently manages requests from Greece and Spain, in addition to those countries mentioned above, for images from the Helios system — of which they are all (except for Germany) co-owners.

All images will be centralized at CMOS before they’re dispatched to clients. In addition to this main SSU center, there will be 29 deployable units and 20 fixed units once the CSO system is fully operational.

The images will be downloadable every 90 minutes — instead of every six hours, as is currently the case with the Helios system — thanks to the Kiruna ground station in northern Sweden, which will be more often be within the satellite’s swath than the CMOS, which is more than 2,000 kilometers further south.

“This will considerably shorten the time lapse between a request being issued and the image being received by the client,” Gilles Chalon, director of the CNES observation service, said at the launch.

The telescope carried by each satellite is more agile than those carried by 14-year-old Helios 2A and 9-year-old Helios 2B, which can only take infrared and black and white images. The newer telescopes mean photos of a particular geographical zone can be taken at a variety of different angles as the satellite passes over the area.

Specific image resolution information is classified, but Jean-Baptiste Pin, director of the MUSIS-CSO program at the DGA French procurement agency, said the CSO-2 will supply images at an extremely high resolution — a level of detail only attainable by airborne captors.

“The quality of the image is without equivalent in Europe,” he said, “but what is important is the agility” of the system. This means that the satellite’s image-taking program can be modified in real time to meet an urgent request.

Chalon explained that he could not describe the focal planes in detail, but said “they are stuffed full of innovations.” He added that the black and white images could be combined with the color images to give analysts a more comprehensive picture.

He also noted that 3D imagery — a capability of the three CSO variants — helps with precision targeting and avoiding collateral damage in a bombing campaign.

CSO is a component of Europe’s €1.75 billion MUSIS, or Multinational Space-based Imaging System. This initiative, born at the end of 2006 and involving Belgium, France, Germany, Greece, Italy and Spain, aims to replace all of Europe’s military and civilian-military space-based observation systems. Today these consist of France’s two optical Helios II military satellites and two optical Pleiades dual satellites; Germany’s SAR-Lupe five-satellite military radar system; and Italy’s Cosmo-Skymed four-satellite dual-radar system. These radar systems allow for observation through thick clouds.

Germany is developing the SARah radar system to replace SAR-Lupe and is also financially participating in the development of CSO-3, while Italy is working on CSG (Cosmo-Skymed Second Generation) as well as a common interoperability layer, which will render the CSG and CSO interoperable. Spain is working on a wide field-of-view optical component known as Ingenio.

RELATED

Pin said the objective was to “avoid any capacity gap at the end of Helios II,” whose lifespan was set at five years. The COS satellites' lifespan is 10 years.

The MUSIS partners will have joint and federated access to a new generation of space-based observation capabilities. However, bilateral agreements, such as the one signed between France and Sweden, will allow other European nations to join.

Wednesday’s launch also marked the first step in the French Armed Forces Ministry’s five-year, €3.6 billion plan to completely renovate its spaceborne capabilities.

As part of this space strategy France will in 2020 launch three CERES — electromagnetic, military and intelligence gathering satellites. By 2022, France will launch the first two of three Syracuse IV military communication satellites with the third ready by 2030. From 2024, the armed forces' satellite navigation system will be modernized under a program called Omega, which will bring an autonomous geolocation capability able to use both GPS and the signal from Galileo, a European Union satellite navigation system.

The director of the DGA, Joel Le Barre, has promised to “open these programs to our European partners.”

Christina Mackenzie was the France correspondent for Defense News.